Why we’re losing land in the Kalayaan Islands

FEATURED IMAGE: BEACH PROFILING. Researchers from the Geological Oceanography Laboratory use the Emery method to measure beaches in the Kalayaan Island Group. Photo courtesy of Jeffrey Munar.

Flooding is not the only problem made worse by the rise of sea-level. Increasing rates of sea-level rise have been reported worldwide, and Manila has long joined the list of ‘sinking cities’ alongside Jakarta, Bangkok, Venice, and Miami. But research from the UP Marine Science Institute’s Geological Oceanography Laboratory shows that this isn’t the whole story.

The coasts of the Philippines are not just overwhelmed by sea-level rise. Our beaches are also eroding away.

“Overall, coastal erosion is dominating,” said Dr. Fernando Siringan, who has studied coastal erosion in the Philippines for over 30 years.

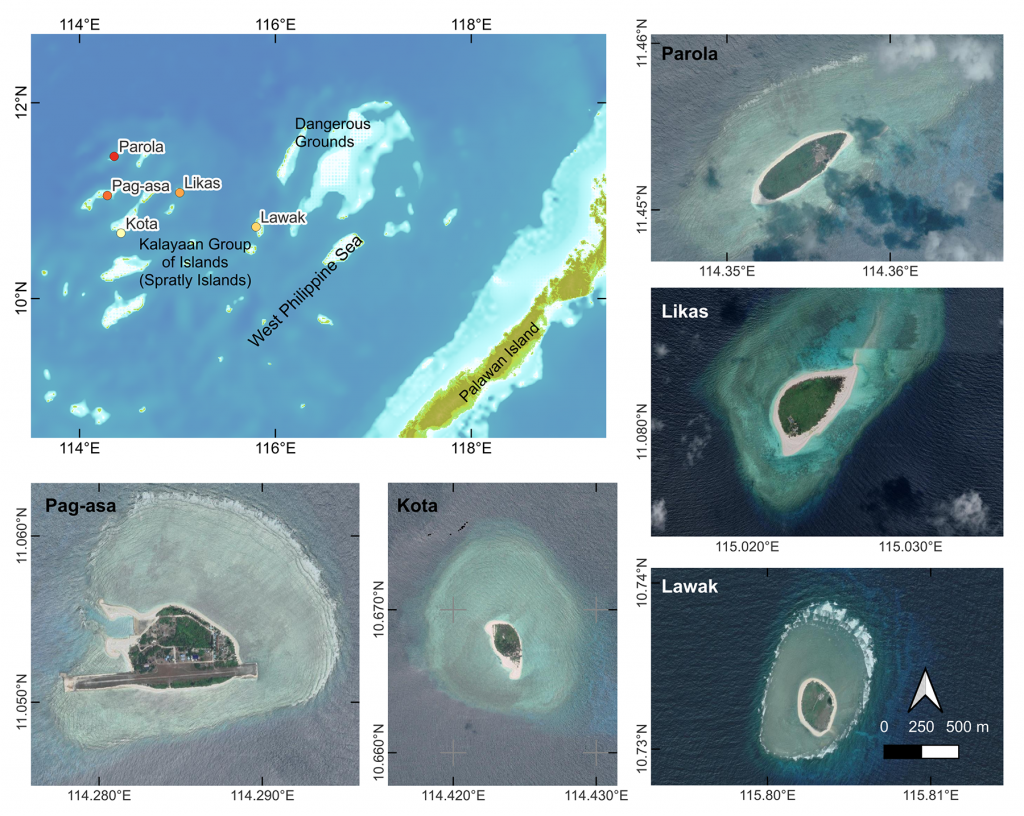

Dr. Siringan’s latest research focuses on the beaches of the West Philippine Sea, for the Resource Inventory, Valuation and Policy in Ecosystem Services under Threat: The Case of the West Philippine Sea (RE-INVEST WPS) project. He works with the Socio-Economics Research Division of the Department of Science and Technology – Philippine Council for Agriculture, Aquatic, and Natural Resources Research and Development (DOST-PCAARRD). By walking these shores and using satellite imagery, his team of scientists mapped how coastal erosion changed the islands of Lawak, Likas, Kota, Pag-asa, and Parola since 2005.

In nature, coastal erosion happens when there is a deficit in the sediment budget: a greater amount of sediment gets carried away by currents, runoff, and winds than what gets supplied to the beach. This sediment loss can be enhanced by man-made structures, such as piers and groins. These structures block the currents moving along the coast. Sediment gets trapped on one side and depleted on the other, causing erosion.

Over the past two decades, Pag-asa has been losing 1500 m2 per year. It is the most eroded of the islands studied, which project researcher Anne Drew Carillo attributes to solid-based man-made structures jutting out of the coastline.

The other islands were faring better, but not by much. Lawak was losing 440 m2 every year, while Likas was losing 740 m2 and Kota was losing 410 m2.

For very small islands like these, the numbers are massive. In addition to sea-level rise caused by global warming, offshore reef islands are slowly drowned by their subsiding nature as atolls.

In contrast, Parola gained land. Dr. Siringan explained that it is the consequence of destructive human activities that unintentionally released sand from the reef flat.

Though this land gain might look beneficial, the effects of human activities on local biodiversity must not be ignored. The destruction of coral reefs in the area displaced fish, invertebrates, and other marine life from their natural habitat — negatively impacting fisheries in the area. Most damningly, the land gained from this release of sand is only temporary.

Losing the corals only makes Parola more vulnerable to coastal erosion in the future. As project researcher Jeffrey Munar explained, “If the area of human activity-damaged sites off Parola is not reoccupied by corals, then a shift to a more erosional state will take place.”

In the Philippines, many beaches are formed by currents bringing in the remains of many coral reef-dwelling organisms such as corals, calcified algae, mollusks, crustaceans, echinoderms, and the single-cell protists Foraminifera. Coastal erosion in coral reef beaches is naturally addressed when sediments from the reefs flow in to replace the eroded beach.

It is our thriving biodiversity that sustains the iconic white sands of Boracay, Palawan, and other popular tourist destinations. A healthy reef also protects the coast, as corals can weaken strong waves before they reach the shore. Weaker waves means less force that would erode the coast.

“Kailangan mabawi [ang coast],” said Dr. Siringan. “We need to improve the health of coral reefs para ang wave protection at sediment source functions nila ay maibalik.”

Dr. Siringan’s takeaway from the Kalayaan Island Group studies is that coastal erosion can be slowed down as long as sediments keep pouring in.

The problem is that man-made structures are blocking the currents that naturally resupply sediment. Added to that are the threats on coral reefs and the protection and sediment supply they provide. The integrity of our coasts are compromised.

The larger goal of Dr. Siringan’s research is to find sustainable ways to maintain island integrity. The fast rate of sea-level rise in the Philippines makes it all the more important to slow land loss from coastal erosion.

“Ma-target lang natin [ang pag-maintain ng islands], okay na,” said Dr. Siringan. “Pero syempre, mas maigi na lumaki siya. ‘Yan ang kwento ng coastal erosion sa West Philippine Sea.”

This article on coastal erosion in the West Philippine Sea uses data from the Geological Oceanography Laboratory’s project reports for RE-INVEST WPS and “Coastal Erosion Management in the Philippines: A Guidebook” by Dr. Fernando Siringan, Ma. Yvainne Sta. Maria, and Johannah Camille Jordan.

RE-INVEST WPS is a three-year project funded by DOST-PCAARRD, which is co-implemented with the UPLB Interdisciplinary Studies Center for Integrated Natural Resources and Environment Management and UP Institute for Maritime Affairs and Law of the Sea.