The Case For Marine Scientific Research in the Philippines

Experts discussed challenges and opportunities in the approval process and framework for marine scientific research (MSR) under international law as the Philippines continues to develop its MSR capability.

Last March 2, 2022, the three-part “Track 1.5 Dialogue on Marine Scientific Research (MSR)” webinar series launched its first session. It was organized by the University of the Philippines Marine Science Institute (UP MSI), Foundation for the National Interest (FNI), the Marine Environment and Resources Foundation (MERF), and the United States Embassy in the Philippines. Dr. Charmaine Willoughby, international relations expert from the De La Salle University, and Dr. Gil Jacinto, retired professor from the UP MSI, served as moderators for the discussions.

Government, Policy, and Law were the focus of the first panel of discussions, while Science and Research were of the second panel.

U.S. Embassy in the Philippines’ Chargé d’Affaires ad interim Ms. Heather Variava welcomed the audience with a message emphasizing the role MSR plays in reducing and preparing for the changes brought on by climate change and environmental damage. She discussed the value of international marine research to help people better understand the threats of biodiversity loss, coral damage, and water quality changes. She also mentioned that improved maritime domain awareness and robust protection of environmental crimes are critical to ensuring the survival of the Philippines’ marine ecosystem for future generations.

MSR and the Law of the Sea

MSR spans a range of scientific fields that study the oceans, their physical properties, and marine life. It has proven to be essential through the years with many contributions to human development, from food and medicine to energy. Through the study of the marine environment and the understanding of the many factors that affect it, its ecosystems are better protected with continued sustainable management.

MSR was widely unregulated until the 1950s when the international community agreed to introduce a legal regime that requires coastal state consent for the conduct of research on the continental shelf.

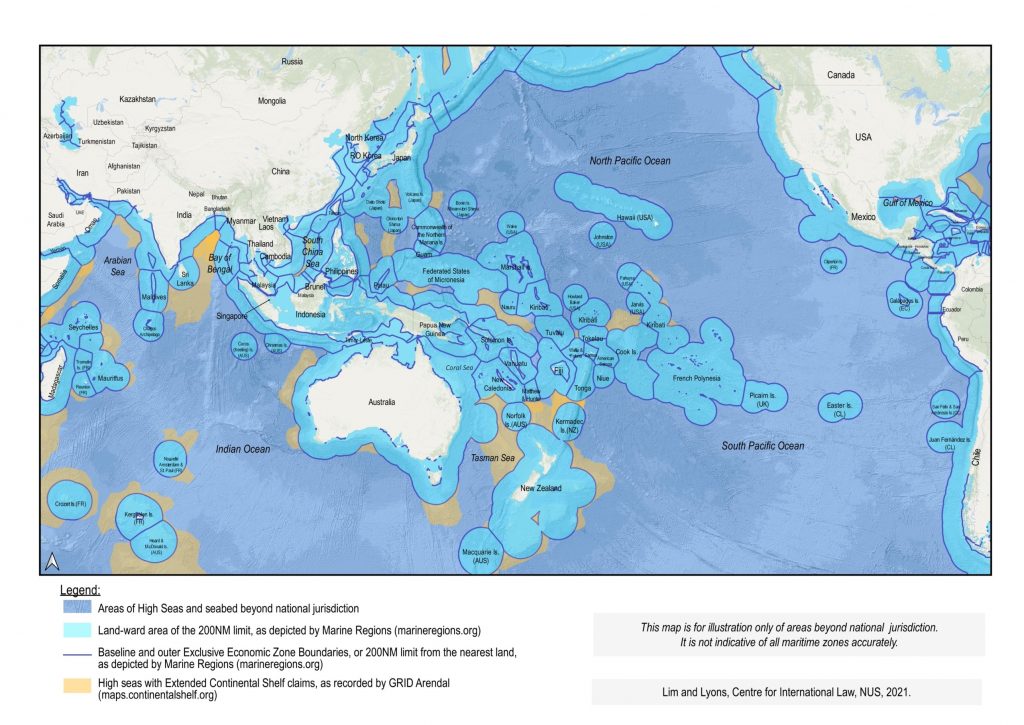

Today, the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) serves as a legal framework that administers activities involving the world’s oceans. Since its enactment in 1982, one of the established freedoms of the convention is the freedom of scientific research on the high seas, making it a guiding principle in conducting MSR.

In the first panel discussion on government policies and regulatory framework in conducting MSR, the featured speaker was Dr. James Kraska from the US Naval War College. Those who gave their reactions based on their experiences were Dr. Ahmad Almaududy from the Indonesian Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Ms. Youna Lyons from the National University of Singapore – Center for International Law, and Mr. Christopher Madrigal, an independent consultant in the Philippines.

To start, Dr. Kraska explained the general principles of MSR, what is and what is not MSR, its broad definitions, and the process of conducting it in the territorial seas of coastal states under the UNCLOS.

He adds that there is no specific definition of what constitutes marine scientific research in the law of the sea convention aside from the standard that it must be conducted for peaceful purposes and not to be used for armed conflict or aggression. Dr. Kraska says that it must only be for the pursuit of more knowledge for all mankind. He then further interprets that MSR must be disseminated widely as an open source so that all states may benefit from it, especially because we all rightfully share the marine environment.

Dr. Kraska also mentioned the different challenges that researchers are faced with, including the lack of consent from coastal states and the national security concern in the South China Sea (SCS) region due to countries that have been asserting ‘rights protection.’ Lastly, he pointed out opportunities for countries like the Philippines to maximize MSR by undergoing large multilateral research programs. Although programs like these can still pose disagreements among states, it can also be taken as a challenge to assert good diplomacy.

One of the first reactors, Dr. Almaududy, proposed the importance of a unified MSR regulation between neighboring maritime nations such as the Philippines and Indonesia — one that implements legal frameworks. He also believes that benefit sharing in MSR must be observed under the international law of common heritage of mankind.

According to Atty. Lyons, the country must assess the environmental impact of MSR, especially during multiple expeditions in the same area, which may continually exploit resources during research activities. She recommended that data acquired from MSR be shared with other states to advance research in the region.

With his vast experience working with the national government on MSR policy, Mr. Madrigal expressed his views on the state of MSR in the Philippines. He said that garnering more support for MSR from policymakers can be difficult due to the focus of the national development discourse being land-centric instead of archipelagic. But he also stated that steps are being taken by the government to establish transparency in the application process with the institutionalization of the revised foreign MSR application guidelines. While there is still much work left to be done in terms of tracking, monitoring, and collating MSR information, Mr. Madrigal considers this to be a way for different stakeholders to collaborate.

Strengthening MSRs in Philippine Waters

The Philippines is in the process of upgrading its capacity for marine research by building its own National Academic Research Fleet (NARFleet) under the Upgrading Capacity, Infrastructure, and Assets for Marine Scientific Research in the Philippines (UPGRADE CIA). Among the program’s long-term proposals is to distribute these vessels and assets to state universities and colleges (SUCs) and higher educational institutions (HEIs), particularly those outside the capital, to study our waters.

The second panel discussion, led by Dr. Alan Jamieson from the University of Western Australia, focused on scientific approaches and research practices in MSR. Mr. Romain Troublé from Tara Expeditions Foundation, Mr. Gregory O’Brien from the Office of Ocean and Polar Affairs of the US Department of State, and Dr. Mohd Uzair bin Rusli from the Institute of Oceanography and Environment – Universiti Malaysia Terengganu were the reactors.

Dr. Jamieson gave a summary of his MSR experience in different exclusive economic zones (EEZs) of various countries. According to him, each country has a different process when conducting MSR, despite UNCLOS. He further mused that scientific work can be simple, productive, and fun just as much as it is complicated, bureaucratic, and even highly politicized, recounting various experiences where local scientists and governments demand either authorship or ownership of the research data.

Before closing his presentation, he gave a few recommendations to researchers on how to navigate the system including, remembering that not all MSR is controversial, looking at different ways to make the system more efficient, and making sure that you’re working with the right people.

He strongly advised concentrating on people—building strong relationships founded on trust, friendship, and networks instead of money, politics, and authorship.

Mr. Troublé shared similar experiences, saying that he too has had trouble collaborating with coastal states, especially in terms of streamlining processes. He ended by saying that more data, tools, and technologies are needed to understand marine biodiversity, which is why regulation on MSR is important.

As a Senior Oceans Policy Advisor who works in processing applications for MSR in the US and oversees research by US scientists, Mr. O’Brien expressed the different challenges faced by researchers, specifically ones that pose a financial and planning burden, like the imposition of fees on mineral, gas, and oil research, as well as on non-commercial research, visa requirements, and custom duties on equipment. He said that on the agency side, the system needs to improve in terms of maintaining awareness throughout the whole process, especially when authorities in charge of the MSR approval process are frequently changed.

The last reactor was Dr. Mohd Uzair who talked about how government agencies hesitate to approve research permits by foreign scientists because they are often seen as “parachute scientists.” He reiterates the importance of building networks among approving agencies, understanding their point of view, and communicating how the MSR will have an economic advantage.

Working towards healthy Philippine seas for future generations of Filipinos

The dialogue was organized with the UN Decade of Ocean Science for Sustainable Development in mind. For the past decades, we have been seeing a rapidly changing ocean that is riddled with the long-term effects of climate change and human activity, impacting marine ecosystems, coastlines, and coastal communities.

Now, more than ever, there is a great need for scientific research to monitor, explain, and understand these changes. The knowledge gained from research can be used to plan nature-based solutions for climate change adaptation and for the sustainable management and conservation of marine resources.

The program was closed by UP MSI Director Dr. Laura David. She thanked the speakers for their time and for sharing valuable lessons with other researchers, reminding them that the ocean is a common heritage, therefore everyone will benefit from shared data and collaborative studies.